From misdiagnosis to mission: Breast cancer survivor turns pain into purpose with hand-knit prostheses

Mary Mwangi has transformed profound pain into purpose, offering hope to women facing cancer, stigma, and loss, while restoring dignity and rebuilding lives through her work.

For eleven long months, Mary Mwangi endured treatment for what she had been told was tuberculosis.

Despite changing medications, her pain persisted, her health worsened, and what was meant to be a path to recovery became a confusing and uncertain journey.

More To Read

- 10 runners race up Mt Kenya in 10 hours to honour women lost to cervical cancer

- Study shows women under 50 face higher risk of colon growths from ultra-processed foods

- KUTRRH introduces groundbreaking nuclear therapy for advanced prostate cancer

- Over 29,000 Kenyans die of cancer yearly as high costs force them to abandon treatment

- Study reveals why colorectal cancer resists immunotherapy

- Over 100 facilities accredited by SHA to provide cancer care after protests

“My journey began in 2016. I had no warning signs. One morning, as I reached for a sugar dish, I suddenly collapsed. I screamed—I thought I’d had a stroke. I was bent over and couldn’t get up.”

After numerous hospital visits, Mwangi was diagnosed with spinal TB and placed on treatment for 11 months. But rather than improving, her health continued to deteriorate.

Determined to find answers, she sought a second opinion and was referred to an oncologist. An MRI recommended two tests, but only one was done, based on symptoms. Eventually, another opinion revealed the truth: she had cancer.

“When I finally got the correct diagnosis, I felt a strange sense of relief. The anxiety of not knowing was overwhelming. My right side was constantly in pain—I just needed clarity so I could begin to fight the right battle.”

She was diagnosed with spinal cancer and immediately began radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Breast cancer

Just when she thought she had started to fight back, life dealt her another blow. In 2017, while taking a shower, she felt a lump in her breast. A new round of tests confirmed her greatest fear: she had stage 3 breast cancer.

“I was crushed. I didn’t want to go through it again. The spinal treatment hadn’t helped, and I had lost faith. I was exhausted, mentally and emotionally. But my family stood by me, and that gave me the strength to keep going. I didn’t want to let them down.”

Tragically, the diagnosis came the same month a close friend, who had undergone a mastectomy for breast cancer, passed away after the disease spread to her lungs.

“I thought I was next. I prepared myself for death. I told myself that maybe I’d be unconscious when it happened—that made it less frightening. I didn’t want any more treatment. Cancer breaks you—it drains you emotionally, mentally, and financially,” Mwangi says.

Total mastectomy

In March 2018, she underwent a lumpectomy in hopes of saving the breast, but post-operative tests revealed advanced cancer, leading to a total mastectomy.

“Losing my breast was heartbreaking. I didn’t know what to wear. I couldn’t even put on a bra. I imagined myself hiding under scarves for the rest of my life. A mastectomy strips a woman of her dignity—you don’t feel like you fit in society anymore.”

Other Topics To Read

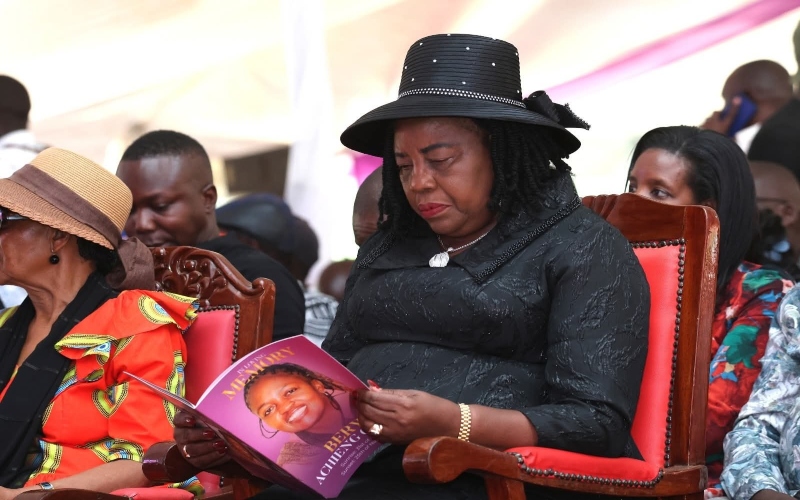

Mwangi taught herself to knit prostheses through YouTube before receiving formal training and launching her boutique business with support from organisations such as KENCO and Kilele. (Photo: Justine Ondiki)

Mwangi taught herself to knit prostheses through YouTube before receiving formal training and launching her boutique business with support from organisations such as KENCO and Kilele. (Photo: Justine Ondiki)

A turning point came when a friend introduced her to a support group, where she bought a silicone prosthesis for Sh22,000. It helped her feel whole again—but the cost sparked a question: What about women who couldn’t afford one?

“I knew I was lucky to afford that prosthesis. But so many women aren’t. Many fall into depression after a mastectomy. Society has made them believe that without a breast, you’re less of a woman.”

Mwangi remembers a day someone visiting her was told, “You’re looking for the woman with one breast.” It stung. But rather than retreat, she turned her pain into purpose.

She noticed how other survivors often walked hunched over, covered with scarves, hiding from the world. She wanted to change that.

Before her illness, Mwangi had learned to knit in high school but never took it seriously—until bed rest from spinal cancer inspired her to pick it up again, asking friends to bring her yarn.

By the time she recovered, she had made over 200 items.

Hand-knit breast prostheses

After completing her breast cancer treatment, she met a speaker through a support group who helped connect her to Kenyatta National Hospital, where she made her first donation of hand-knit breast prostheses.

“At first, I just wanted to help. But a friend told me that for this to be sustainable, I needed to think bigger—to turn it into a business. That’s how the idea was born.”

Mwangi taught herself how to knit prostheses from YouTube, and she later received formal training. She launched her small boutique business with support from organisations like KENCO and Kilele.

Today, she sells each prosthesis for Sh1,000, offering them at half the price to partner organisations that donate to breast cancer survivors.

She has trained fellow survivors in places like Thika, empowering them not just with support, but with skills to earn a living.

"In January, I trained several women. Just last week, we sold 120 pieces. That’s how I started the New Dawn Support Group—to walk with other survivors, caregivers, and families. We help them navigate hospitals, access support, and rebuild their lives,” she says.

Pain into purpose

Mwangi has transformed profound pain into purpose, offering hope to women facing cancer, stigma, and loss, while restoring dignity and rebuilding lives through her work.

“If your loved one is diagnosed with cancer, please love them, support them, and welcome them back. Help them reintegrate into the community. Let’s end the stigma and see survivors for who they are—strong, beautiful, and whole.”

Dr Andrew Odhiambo, a medical oncologist at Prime Cancer Care Clinic, emphasises that while mastectomy can be a life-saving intervention, it comes with significant emotional and psychological weight for many patients.

"Sometimes, mastectomy is the only option for survival. In these cases, we ensure that patients receive thorough counselling and emotional support to help them face this difficult decision with clarity and strength," he explains.

One of the most pressing challenges Odhiambo and his team encounter is body dysmorphism—a deep struggle with appearance and identity following surgery.

"Body image issues profoundly affect our patients," he says. "It impacts their ability to work, socialise, and maintain relationships. We’ve even seen marriages and partnerships collapse under the emotional strain."

Emotional tunnel

Although the emotional impact is significant, often placing patients in what Odhiambo describes as an "emotional tunnel", he notes that it usually does not interfere with treatment adherence.

"Despite everything, patients understand the seriousness of cancer and remain committed to their treatment plans."

Preparing patients for surgery involves more than medical briefings. It is a collaborative, multidisciplinary process that brings together oncologists, breast surgeons, reconstructive surgeons, and counsellors.

Odhiambo stresses the importance of not only delivering the medical facts but also ensuring patients feel informed and empowered.

"It’s not enough to tell a patient they will lose their breast. We must walk with them, present alternatives, and offer a clear picture of what life can look like afterwards."

Reconstruction options

Patients are guided through various reconstruction options, including silicone implants and tissue reconstruction using muscle from other parts of the body. Thanks to modern advancements, these methods often achieve natural-looking results.

Crucially, Odhiambo points out that not all patients require a mastectomy. In some cases, breast-conserving surgery is an effective alternative with similar survival outcomes.

"When patients are extremely anxious about undergoing a mastectomy, we invest in extensive counselling. We take time to help them understand the benefits, prepare for recovery, and envision life after surgery. This prevents rushed or misinformed decisions," he says.

Stigma

Stigma remains one of the most damaging barriers in the fight against cancer. According to Odhiambo, it fosters fear, delays diagnosis, and can lead patients to make choices that hurt their chances of survival.

"Stigma feeds off fear and ignorance, and when people are afraid to seek information, they get stuck in a harmful cycle. The more stigmatised they feel, the less likely they are to learn the facts—and that ignorance leads to more suffering," he says.

According to the National Cancer Institute of Kenya, breast cancer is the most common type of cancer among women in the country, representing approximately 23.3 per cent of all cancer cases diagnosed in women.

Each year, an estimated 6,799 women in Kenya are diagnosed with breast cancer, and around 3,107 succumb to the disease.

The World Health Organisation reports that in 2022, breast cancer affected 2.3 million women globally, making it the most common cancer among women. It also caused around 670,000 deaths, accounting for 6.9 per cent of all cancer fatalities.

Top Stories Today